Fashion: Sartorial Opiate or Shamanistic Magic?

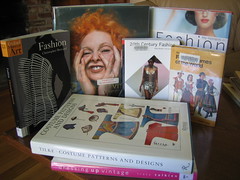

New word: sartorial means pertaining to tailoring. The history of consumerism is embodied in the glamorous, eye candy history of fashion. These writers have more direct awareness of the relationship between fashion and imperialism than most economists. Where economists seem to accept industrial growth and expansion as a good that will raise all boats, these art historians and cultural observers touch on the darker underpinnings of an elitism that could not survive without cheap labor to shore up the expensive tastes of its wasteful leisure classes. Christopher Breward, author of "Fashion", from the Oxford History of Art series, is particularly insightful in this regard.

From his rather dry account, I learned that "dynamic obsolescence" was invented by fashion stylists beginning in the mid 19th century with the concept of the fall and winter collection which aggressively rendered last seasons fashion out of style. Obsolescence is of course the driving growth of virtually all industries today.

Fashion being the most portable and accessible of cultural markers was spread from the three key cities: London, Paris and New York via print media, the fashion show and later film and television to other cities aspiring to rank as global players. (The fashion show was big in Bangkok where it was usually associated with royalty. I was a runway model for two of these events at the home of local royalty when I was five and six years old.)

So I was intrigued to learn that it is mainly in the West that fashion was ever changing while elsewhere it was static due to local customs and social hierarchies. This does parallel the rise of the cult of the individual in the West, but I would go further and look at the religious beliefs that allowed this cult of the individual to arise. Buddhism, for instance, with its teachings of no self would not lend itself to the cultivation of individualism and still doesn't, not with the skill of personal power that Western psychology has elevated it to.

But I am not in a hurry to label fashion as a tool of imperialist Western selfishness. These accounts of fashion also point out the influence of street fashion from the 19th century dandy to the Punk styles of the '70s. Vivienne Westwood, whose fashion footsteps I seem to be following, is credited with firing up the whole phenomena of Punk. She then went on to fuse 16th century, ie Renaissance clothing cuts, with modern materials and gender bending presentation. Fashion was certainly a part of the emancipation of women, had a hand in popularizing cycling and has been the visual marker of all kinds of anti-establishment movements including queer culture. It has been as much a tool of the outsider in communicating resistance as it has been a tool of the elite to dictate the parameters of the in crowd.

But to go even deeper, I remembered from the novel "The Mists of Avalon" that glamour is a word borrowed from witchcraft. Thus glamour is a concept used by witches to enhance spells that require the viewer to be enchanted by the appearance of the witch herself. (Kind of a sleight of hand like the use of the Force in Starwars when Obe One persuaded Stormtroopers to allow him entry through a security checkpoint.)

In this sense it could be said that fashion is akin to the use of hallucinogenic drugs. Where drugs were once an important part of shamanistic ritual, they are now taken without the ritual and have become portals to addiction. Thus fashion has become a portal for consumer addiction. But rather than take the puritanical route and declare a "fashion free" zone, I would prefer to reclaim fashion as an inspirational art force that requires a constant stream of creative manifestations to communicate ideas and ideals, but it would also have to be done without compromising values of sustainability. And I can do that as long as there is already manufactured materials out there to salvage. After that it will be back to the fig leaf.

From his rather dry account, I learned that "dynamic obsolescence" was invented by fashion stylists beginning in the mid 19th century with the concept of the fall and winter collection which aggressively rendered last seasons fashion out of style. Obsolescence is of course the driving growth of virtually all industries today.

Fashion being the most portable and accessible of cultural markers was spread from the three key cities: London, Paris and New York via print media, the fashion show and later film and television to other cities aspiring to rank as global players. (The fashion show was big in Bangkok where it was usually associated with royalty. I was a runway model for two of these events at the home of local royalty when I was five and six years old.)

So I was intrigued to learn that it is mainly in the West that fashion was ever changing while elsewhere it was static due to local customs and social hierarchies. This does parallel the rise of the cult of the individual in the West, but I would go further and look at the religious beliefs that allowed this cult of the individual to arise. Buddhism, for instance, with its teachings of no self would not lend itself to the cultivation of individualism and still doesn't, not with the skill of personal power that Western psychology has elevated it to.

But I am not in a hurry to label fashion as a tool of imperialist Western selfishness. These accounts of fashion also point out the influence of street fashion from the 19th century dandy to the Punk styles of the '70s. Vivienne Westwood, whose fashion footsteps I seem to be following, is credited with firing up the whole phenomena of Punk. She then went on to fuse 16th century, ie Renaissance clothing cuts, with modern materials and gender bending presentation. Fashion was certainly a part of the emancipation of women, had a hand in popularizing cycling and has been the visual marker of all kinds of anti-establishment movements including queer culture. It has been as much a tool of the outsider in communicating resistance as it has been a tool of the elite to dictate the parameters of the in crowd.

But to go even deeper, I remembered from the novel "The Mists of Avalon" that glamour is a word borrowed from witchcraft. Thus glamour is a concept used by witches to enhance spells that require the viewer to be enchanted by the appearance of the witch herself. (Kind of a sleight of hand like the use of the Force in Starwars when Obe One persuaded Stormtroopers to allow him entry through a security checkpoint.)

In this sense it could be said that fashion is akin to the use of hallucinogenic drugs. Where drugs were once an important part of shamanistic ritual, they are now taken without the ritual and have become portals to addiction. Thus fashion has become a portal for consumer addiction. But rather than take the puritanical route and declare a "fashion free" zone, I would prefer to reclaim fashion as an inspirational art force that requires a constant stream of creative manifestations to communicate ideas and ideals, but it would also have to be done without compromising values of sustainability. And I can do that as long as there is already manufactured materials out there to salvage. After that it will be back to the fig leaf.